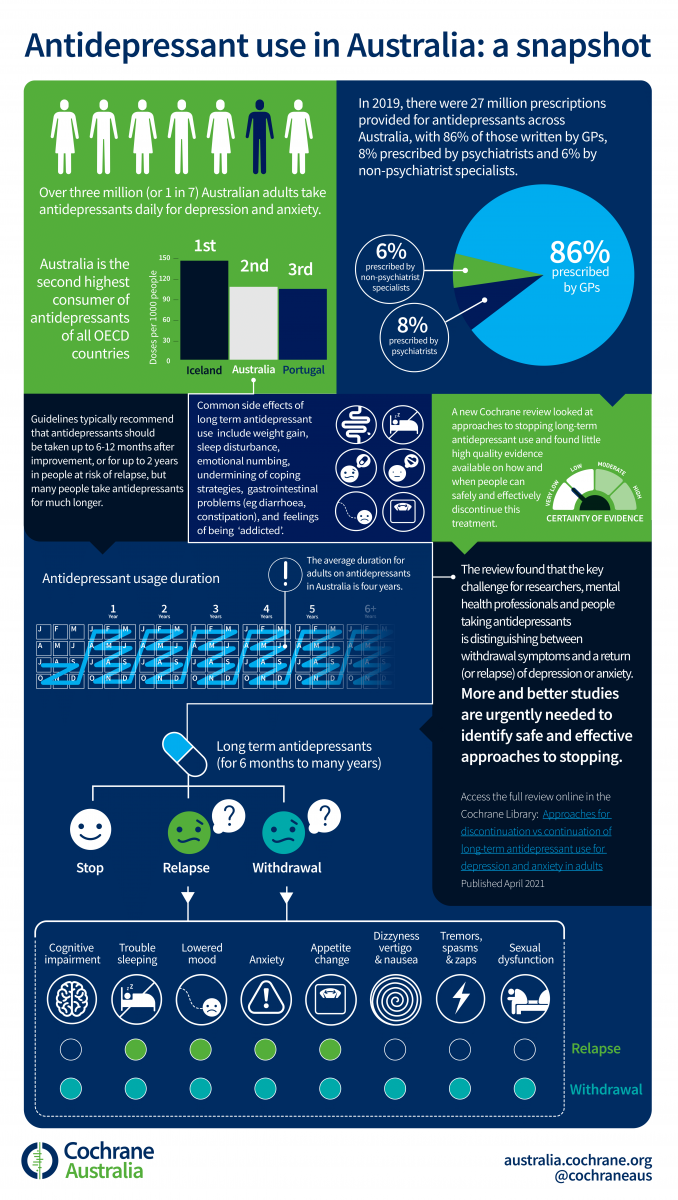

Antidepressants are widely used for depression and anxiety. Guidelines recommend that an antidepressant should be continued for at least six months after people start to feel better, and for at least two years if they have had two or more periods of depression. Many people take antidepressants for much longer. Ellen Van Leeuwen and Mark Horowitz, authors of a recently published Cochrane review on approaches for discontinuing antidepressant use, answer some questions about the findings of the review.

Tell us about this Cochrane Review, why did you think it was important to do it?

Ellen: The rise in long-term antidepressant use is a major concern. For example, in the UK, nearly half of people using antidepressant (8% of the total population, approximately 3.7 million people) have been taking them for more than two years. Antidepressants that, despite initially being appropriate, are not discontinued after the recommended duration can lead to unnecessary harm and costs.

Mark: Antidepressants can put people at risk of adverse events such as sleep disturbance, weight gain, sexual dysfunction and gastrointestinal bleeding, as well as feeling emotionally numb and what they described as feeling “addicted,” because they cannot easily stop the medication. This is because people’s brains physically adapt to antidepressants after long-term use (called physical dependence). They may also impair patients’ autonomy to deal with problems in their life without medication. Guidelines recommend that antidepressants should be taken up to 6 to 12 months after improvement and 2 years after improvement in people at risk for relapse.

Ellen: As a GP I see many patients struggling with coming off antidepressants that they have been taking long-term. However, I was surprised that there wasn’t a Cochrane review on discontinuing long-term antidepressants, so I started this review. We included all studies comparing approaches for discontinuation with continuation of antidepressants (or usual care) for people who are prescribed antidepressants for depression or anxiety for at least six months.

What can people learn about discontinuation from antidepressants from this evidence?

Ellen: Honestly, the evidence in this area is very problematic. It is not possible to make any firm conclusions about the effects and safety of the approaches for discontinuation studied to date. There were only a few studies with a focus on successful antidepressant discontinuation rate.

The main problem is that studies did not distinguish between symptoms of relapse of depression and symptoms of withdrawal after discontinuation.

Mark: Yes, withdrawal symptoms can include insomnia, low mood, anxiety, changes to appetite, and these symptoms will be recorded on the depression scales used to detect relapse, so they might inflate the rate of relapse recorded in groups that stop antidepressants.

Additionally, most tapering regimes were limited to four weeks or less, in contrast to NICE guidelines recommending tapering over four weeks or more. In fact, there is now increasing recognition that antidepressants might need to be tapered over months or longer than a year to very low doses for long-term users.

Ellen: For me, it was disappointing that the large group of people taking antidepressants in the community (i.e. those with only one or no prior episode of depression) have been under-researched. Most published studies focus on people with recurrent depression. Another finding was that we found very low certainty evidence that high intensity psychotherapy such as mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MB-CT) and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may support people to come off antidepressants. But none of the studies included more scalable and accessible psychological approaches such as online support.

And what can people learn about continuation of long-term antidepressant use?

Ellen: Based on the limitations we have mentioned, we cannot make any conclusion about this, as we were not confident in the evidence we found. We certainly need more de-prescribing studies investigating the harms and the benefits of discontinuation before we can make any conclusion.

Mark: Yes, it is very difficult to interpret existing studies that suggest continuation of antidepressants because they are based on discontinuation studies in which half of the patients are stopped – often abruptly or in a few days – compared to a group that continues their antidepressants. This means we can’t be sure whether the group who stopped got worse because of withdrawal symptoms or genuine relapse. To provide clearer evidence on this, future studies should distinguish carefully between relapse and withdrawal symptoms and follow emerging guidance to use taper schemes of many weeks or months (or longer for long-term users) down to very low doses before stopping. Such studies would give us a clearer idea of the ability of antidepressants to prevent relapse.

Ellen: Additionally, there is an urgent need to include wider representation of patient populations. For example, those people with one or no prior episodes of depression, those with anxiety disorders, and older people including those who take multiple medications (polypharmacy) and those who are frail. Most antidepressants are prescribed by GPs. This review reinforces the call for more research in the primary care setting, particularly for people with low risk of relapse and those for whom there is uncertainty about the benefit of antidepressant treatment.

What is the core message for clinician’s and patients?

Ellen: Overall there remain many uncertainties. However, this review aids clinicians in openly discussing with their patient and with family/carers (as appropriate) the potential benefits and harms of continuing or discontinuing antidepressants including withdrawal.

Mark: Doctors and patients should be aware that withdrawal symptoms from antidepressants are common and can be mistaken for relapse of the underlying condition. Although evidence found in this review is sparse, experiencing withdrawal symptoms is not a sign that the patient needs the antidepressant, but rather a sign that they might need to taper more gradually and down to lower doses before stopping.

What will happen next? Are you planning an update or any subsequent reviews on a linked topic?

Ellen: Celebrating with my team that we made it! No, I am currently working on a PhD of which the review is part of it which I want to defend in 2021. However, I’m continuing further research in the field of long-term antidepressants. One of the recommendations of our review is a further review comparing different discontinuation strategies.

Mark: At the moment there are a few studies happening around the world looking at discontinuing antidepressants, such as the REDUCE trial in the UK, some including somewhat slower tapers than the studies found in this review, going down to lower doses, and so an update to this review may be necessary in the future.

- Read this review on the Cochrane Library

- Visit the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group website

- Listen to the podcast in English and Spanish