In this Evidently Cochrane blog, Sarah Chapman looks at the Cochrane evidence for aspects of routine dental care. Something to smile about? Or are there big gaps…?

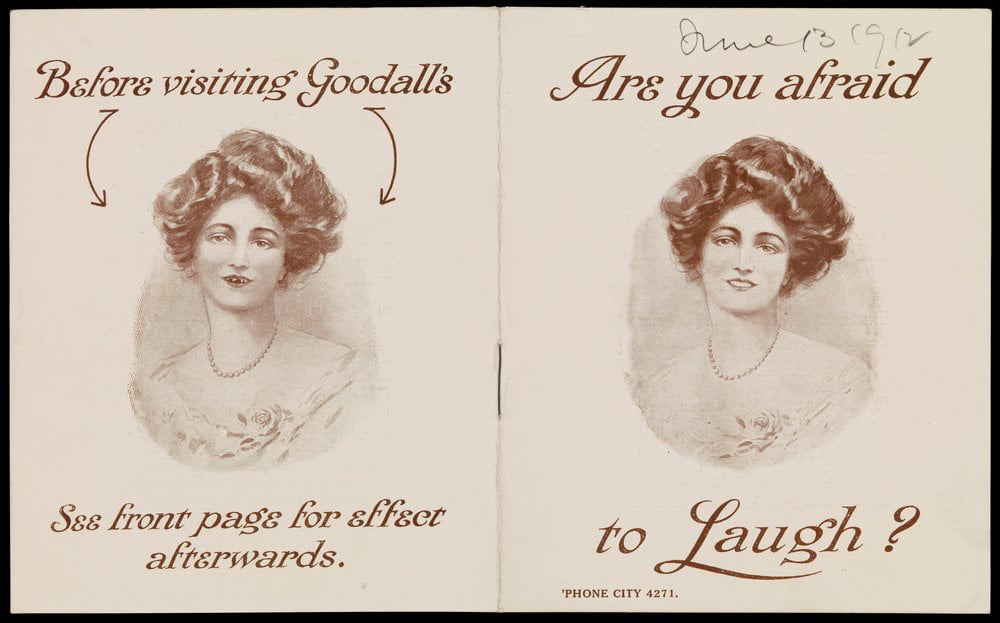

“Are you afraid to laugh?” Goodall’s Dental Institute, 1912. Wellcome Collection.

My grandmother used to tell the tale of when she was a schoolgirl, back in about 1920, and a school event to which parents were invited. Nan and her friend enjoyed a carefree afternoon without their mothers there, having avoided inviting them – the friend because her mother had white hair, and Nan because her mother had just had all her teeth taken out. There was trouble, she recalled, when they were rumbled by a write-up of the event.

Teenagers haven’t changed much in the hundred years since then, but thankfully the state of the nation’s teeth has. My great-grandmother would not have been unusual in having all her teeth removed, to be replaced by an easier-to-care-for set of dentures, and some women even received this as a 21st birthday present! This changed, thanks, in part, to free dental treatment through the NHS from its beginning in 1948, the fluoridation of toothpaste from 1959, improvements in diet and a new emphasis on good dental hygiene.

Today, we are commonly told we should have a dental check-up every six months, and a visit to the dental surgery often includes getting advice from a hygienist on how to care for our teeth and gums, and perhaps a ‘scale and polish’. This routine dental care is all so familiar we may not question it, but we should! What’s the evidence? Does it give us, and our dental health professionals, something to smile about?

How often should you have a dental check-up?

As a child, I loved my regular visits to the dentist. As an infant, I delighted in the toy farm in the waiting room with, joy of joys, a ‘real’ well with a bucket you could wind up; while my teenage dental trips were always followed by a visit to the ice cream parlour (oh dear…)! But is there any evidence behind the common recommendation that we should go every six months? No there isn’t! The Cochrane Review addressing this found just one study with 185 people; insufficient evidence to support or refute that six-monthly recall. This is something that has been debated since the 1970s and we still lack evidence to guide practice!

Oral hygiene advice

A newly published Cochrane Review aimed to address uncertainties about the impact of one-to-one oral hygiene advice (OHA), given by a dental care professional in a dental setting, on our oral health, attitudes and behaviour, by bringing together the best available evidence. Although the review includes 19 studies (randomised trials) with over 4000 people, there was so much variation that the team weren’t able to pool the data, and concluded that “there was insufficient high‐quality evidence to recommend any specific one‐to‐one OHA method as being effective in improving oral health or being more effective than any other method.”

That’s disappointing. So what about that ‘scale and polish’? Is the evidence any better?

Routine scale and polish

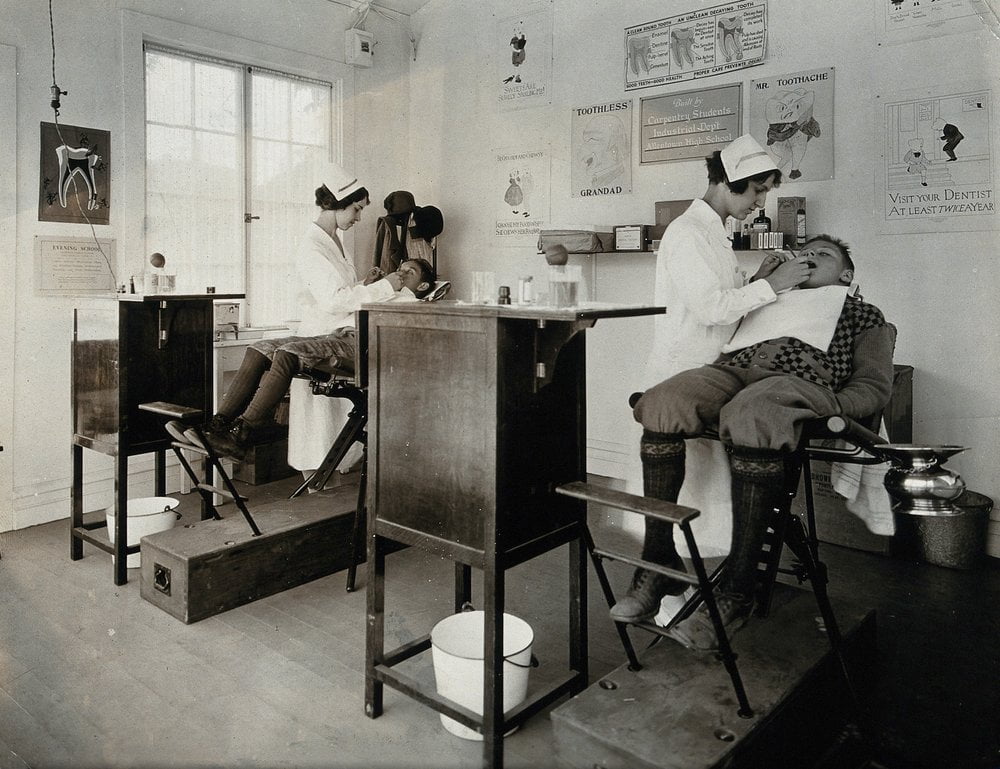

US dental clinic, circa 1920. Wellcome Collection.

Both hygienists and dentists provide scaling and polishing for their patients at regular intervals, even when those patients are at low risk of gum disease. There is uncertainty about whether this is useful and how often it should be done. Along with a sit-down and a chance to reflect on your guilt about not having flossed when you were told to, the ‘routine scale and polish’ offers you the removal of deposits of bacteria called plaque, and hardened plaque known as tartar or calculus, which is too hard for removal by toothbrushing by even the most diligent brushers (I’m looking at my husband, bafflingly motivated by the promise of a digital smiley face after two minutes, on a gadget linked to his toothbrush. He is 55…).

A Cochrane Review team looked for the evidence from randomised trials on routine scale and polish in healthy adults without severe gum disease and found surprisingly little – just three studies with 836 people. The authors note that “given the considerable resources involved in providing this treatment for adults in many countries it is disappointing that there is so little good quality, reliable research evidence available to inform clinical practice.”

This potentially relieves you of guilt if you’re not getting a scale and polish regularly, but it would be very good to have some decent evidence to guide practice, and there is work being done to try to do just this. A randomised trial, mentioned as ongoing in the Cochrane Review, has now been published and you can read about it here. We look forward to seeing this trial incorporated into the next update of the Cochrane Review. They found “no additional benefit from scheduling 6-monthly or 12-monthly PIs [scale and polish] or over not providing this treatment unless desired or recommended, and no difference between OHA delivery for gingival inflammation/bleeding and patient-centred outcomes. However, participants valued, and were willing to pay for, both interventions, with greater financial value placed on PI than on OHA.” This reminds us that patient preference and clinical judgement also play a role and along with evidence these are regarded as the three pillars of evidence-based decision-making.

Flossing?

I have yet to meet a dental hygienist who didn’t advocate flossing, but I really can’t be bothered to do it, and I don’t want to find a reason to add yet another source of plastic to my environmental footprint. Need I feel guilty? There’s a Cochrane Review on flossing too, which includes 12 studies with 582 people, comparing flossing and toothbrushing with toothbrushing alone. All the studies looked at the effects on gum disease and plaque. Once again, there was so much variation between the studies that the data couldn’t be pooled. Whilst there is some evidence that flossing added to toothbrushing may reduce gum disease and plaque compared to just toothbrushing, it is unreliable. For adults, feel free to choose whether or not to floss your teeth, but it’s probably wise to steer clear of this year’s dance trend, or you risk being ridiculed for your flossing, like Jeremy Corbyn at the Pride of Britain Awards.

Check your bathroom shelf

Napoleon Bonaparte’s fancy toothbrush (Wellcome Collection). Would he have been better off with a powered one?

Finally, while good evidence on these elements of routine dental care is lacking, there is evidence to guide us on what we have at home, in those basics of toothbrushes and toothpaste. Something to smile about! A Cochrane Review found moderate-certainty evidence that powered toothbrushes probably reduce plaque compared with manual toothbrushes, in the short- and long-term. (If trialists want to explore the impact of a digital smiley face toothbrushing intervention, I will volunteer my husband.)

Another Cochrane Review has evidence you might want to consider when choosing your toothpaste. It finds that fluoride toothpaste containing triclosan and copolymer leads to a small reduction in tooth decay and is probably more effective at reducing plaque and gingivitis than fluoride toothpaste without those ingredients. As for chlorhexidine mouthwash, you can read all about the Cochrane evidence in this blog by dentist Bosun Hong.

- Join in the conversation on Twitter with @SarahChapman30 @CochraneUK @CochraneOHG or leave a comment on the original blog post.

- References

- Read other Evidently Cochrane blog posts