New evidence published in the Cochrane Library shows that adding calorie labels to menus and next to food in restaurants, coffee shops, and cafeterias could reduce the calories that people consume, although the quality of evidence is low.

Eating too many calories contributes to people becoming overweight and increases the risks of heart disease, diabetes, and many cancers, which are among the leading causes of poor health and premature death.

Several studies have looked at whether putting nutritional labels on food and non-alcoholic drinks might have an impact on their purchasing or consumption, but their findings have been mixed. Now, a team of Cochrane researchers has brought together the results of studies evaluating the effects of nutritional labels on purchasing and consumption in a systematic review.

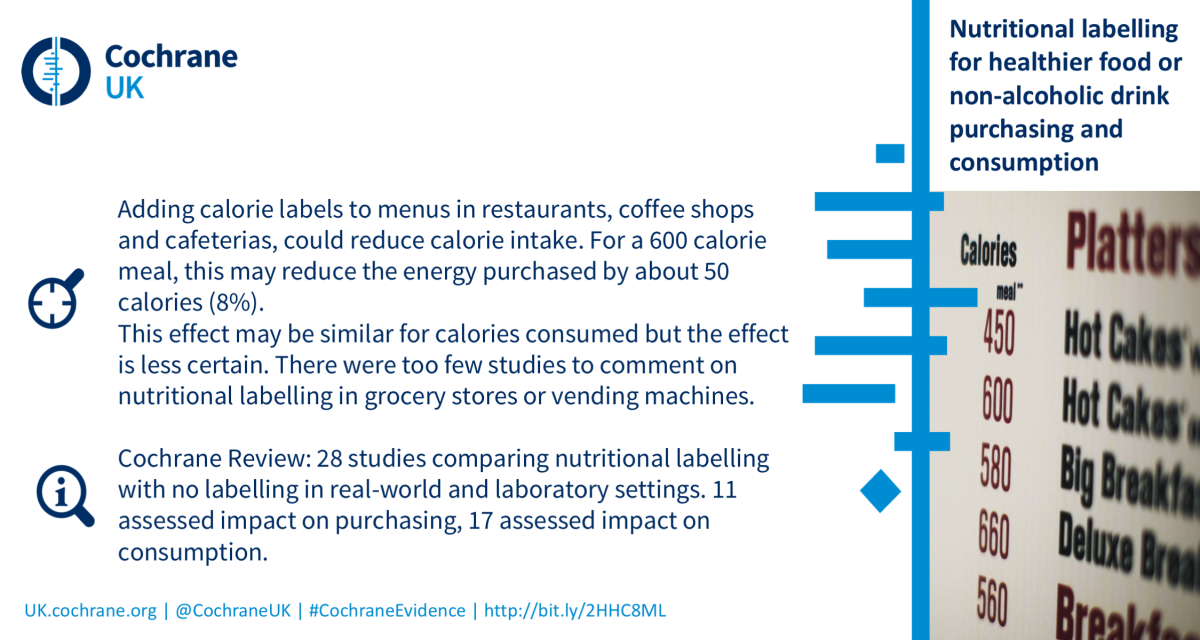

The team reviewed the evidence to establish whether, and by how much, nutritional labels on food or non-alcoholic drinks affect the amount of food or drink people choose, buy, eat, or drink. They considered studies in which the labels had to include information on the nutritional or calorie content of the food or drink. They excluded those including only logos (e.g. ticks or stars) or interpretative colours (e.g. ‘traffic light’ labelling) to indicate healthier and unhealthier foods. In total, the researchers included evidence from 28 studies, of which 11 assessed the impact of nutritional labelling on purchasing and 17 assessed the impact of labelling on consumption.

The team combined results from three studies where calorie labels were added to menus or put next to food in restaurants, coffee shops, and cafeterias. For a typical lunch with an intake of 600 calories, such as a slice of pizza and a soft drink, labelling may reduce the energy content of food purchased by about 8% (48 calories). The authors judged the studies to have potential flaws that could have biased the results.

Combining results from eight studies carried out in artificial or laboratory settings could not show with certainty whether adding labels would have an impact on calories consumed. However, when the studies with potential flaws in their methods were removed, the three remaining studies showed that such labels could reduce calories consumed by about 12% per meal. The team noted that there was still some uncertainty around this effect and that further well-conducted studies are needed to establish the size of the effect with more precision.

The review’s lead author, Professor Theresa Marteau, Director of the Behaviour and Health Research Unit at the University of Cambridge (UK), says: “This evidence suggests that using nutritional labelling could help reduce calorie intake and make a useful impact as part of a wider set of measures aimed at tackling obesity.” She added, “There is no ‘magic bullet’ to solve the obesity problem, so while calorie labelling may help, other measures to reduce calorie intake are also needed.”

Fellow author Professor Susan Jebb from the University of Oxford commented: “Some outlets are already providing calorie information to help customers make informed choices about what to purchase. This review should provide policymakers with the confidence to introduce measures to encourage or even require calorie labelling on menus and next to food and non-alcoholic drinks in coffee shops, cafeterias, and restaurants.”

The researchers were unable to reach firm conclusions about the effect of labelling on calories purchased from grocery stores or vending machines because of the limited evidence available. They added that future research would also benefit from a more diverse consideration of the possible wider impacts of nutritional labelling, including impacts on those producing and selling food, as well as consumers.

Expert reactions to the Cochrane Review:

Professor Ian Caterson, President of the World Obesity Federation, commented: “Energy labelling has been shown to be effective: people see it and read it and there is a resulting decrease in calories purchased. This is very useful to know – combined with a suite of other interventions, such changes will help slow and eventually turn around the continuing rise in body weight.”

Responding to the new Cochrane Review evidence on nutritional labelling on menus in restaurants and cafes, Caroline Cerny, Obesity Health Alliance Lead, said: “Too often food in restaurants or cafes can be a large portion size and packed with hidden ingredients such as salt or sugar, so it’s very easy to eat more calories than you need. It makes sense that when we know the nutritional content of the food we’re eating, the more likely it is that we’ll make healthier choices. This important research shows that clear labelling of the food we eat out of home, as is increasingly on display on supermarket products, is an important step to empowering people to make informed choices when it comes to eating.”

Dr Amelia Lake, Associate Director of Fuse: the Centre for Translational Research in Public Health, and Dietitian and Reader in Public Health Nutrition at Teesside University, said: “As a society we obtain a significant amount of food and drink outside of our home environment. This out of home food environment is incredibly important in determining what we eat. In general there is little evidence about what interventions may be effective in changing our behaviours in cafes, restaurants, takeaways, or even vending machines....[T]his intervention needs to be used alongside other interventions addressing both calorie intake and expenditure. It is one piece of the intervention jigsaw that may help in addressing the obesity crisis.”

Prof Peymané Adab, Professor of Public Health, The University of Birmingham, said: “This is a high standard study which has considered the quality of the underlying research....The overview has shown that higher quality studies are needed to increase our confidence about the benefits of labelling. In particular we don’t know whether those who alter their food purchasing or consumption are those that would most benefit, or whether such labelling could differentially benefit only subgroups of the population, thus widening inequalities. We also don’t know whether nutritional labels could have other impacts, such as substitution with less healthy alternatives or on total calories consumed over a longer time period. Information on calories alone does not tell us about the overall quality of the food (e.g. amount of salt, vitamins etc.) and we need more research to know whether or not choosing lower calorie foods at one point in the day could lead to compensatory overconsumption by choosing something more highly calorific later. Finally, the effects of nutritional labelling on the reformulation of products by food manufacturers and menu choices offered by restauranteurs also need to be studied.”

Prof Brian Ratcliffe, Emeritus Professor of Nutrition, Robert Gordon University, said: "...The evidence is not strong that nutritional labelling, especially of energy (calories), has a significant impact on consumer choice. It is imperative, however, that as much information is given at point of selection so that consumers can make informed comparative choices. If you are watching your weight and one dessert is flagged as 100 kcal (sorbet) while others are around 300 kcal (sticky toffee pudding), then the right choice is clear. Even modest reductions of up to 10% in energy intake when eating out could help individuals who are trying to control their calories.”

Prof Judith Buttriss, Director General, British Nutrition Foundation, said: “It is good news that efforts already being taken by some high street chains to influence calorie intake through provision of information on menus and at the point of sale may have a positive effect. Hopefully this will encourage others to adopt this approach as part of a suite of ‘nudges’ designed to encourage healthier choices."

- Read the full quotes from the experts and their declared interests

- Read this Press Release in Spanish

Related Coverage

- Nutritional labelling on menus helps cut the calories we buy on The Conversation

- What's on the menu? Can nutritional labelling reduce our calorie intake? on Evidently Cochrane

- New evidence suggests nutritional labelling on menus may reduce our calorie intake on The University of Cambridge Reseach news

- Calorie Counts Are Now on Menus Nationwide, But Do They Work? on Health Line

- Visual round-up of new coverage.

Full citation: Crockett RA, King SE, Marteau TM, Prevost AT, Bignardi G, Roberts NW, Stubbs B, Hollands GJ, Jebb SA. Nutritional labelling for healthier food or non-alcoholic drink purchasing and consumption. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD009315. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009315.pub2

For further information, please contact:

Jo Anthony

Senior Media and Communications Officer, Cochrane

M +44(0) 7582 726 634 E janthony@cochrane.org or pressoffice@cochrane.org

Craig Brierley

Head of Research Communications

University of Cambridge

Tel: +44 (0)1223 766205

Mob: +44 (0)7957 468218

Email: craig.brierley@admin.cam.ac.uk

About Cochrane

Cochrane is a global independent network of researchers, professionals, patients, carers, and people interested in health.

Cochrane produces reviews which study all of the best available evidence generated through research and make it easier to inform decisions about health. These are called systematic reviews.

Cochrane is a not-for-profit organization with collaborators from more than 130 countries working together to produce credible, accessible health information that is free from commercial sponsorship and other conflicts of interest. Our work is recognized as representing an international gold standard for high quality, trusted information.

If you are a journalist or member of the press and wish to receive news alerts before their online publication or if you wish to arrange an interview with an author, please contact the Cochrane press office: pressoffice@cochrane.org

About the University of Cambridge

The mission of the University of Cambridge is to contribute to society through the pursuit of education, learning and research at the highest international levels of excellence. To date, 98 affiliates of the University have won the Nobel Prize.

Founded in 1209, the University comprises 31 autonomous Colleges, which admit undergraduates and provide small-group tuition, and 150 departments, faculties and institutions. Cambridge is a global university. Its 19,000 student body includes 3,700 international students from 120 countries. Cambridge researchers collaborate with colleagues worldwide, and the University has established larger-scale partnerships in Asia, Africa and America.

The University sits at the heart of the ‘Cambridge cluster’, which employs 60,000 people and has in excess of £12 billion in turnover generated annually by the 4,700 knowledge-intensive firms in and around the city. The city publishes 341 patents per 100,000 residents.